What 1850 Taught Me About Leadership Today

For the last month or so, I’ve been at my desk by 4:30 a.m.! I’ve been doing this because I couldn’t find another time to carve out 90 minutes to learn the material to help my church, Mother Bethel AME, maintain proper coverage for the museum in the church’s basement. You might recall that I recently shared that I had completed docent training for the Barnes Foundation. I figured I may as well make this summer the “throwback to college” summer—and spend it reading.

This morning, I was studying the life of Richard Allen, founder of the AME denomination, whose second wife, Sarah Bass, died at age 85 in 1849. That’s when my morning study got derailed.

I wound up at leadership and structural harm!

Initially, I searched life spans by race and gender around 1850. Then, I searched for causes of death in Philadelphia. Consistently, I found the following:

- White women: TB & childbirth

- White men: TB & pneumonia

- Black women: Dysentery, childbirth, malnutrition

- Black men: Dysentery, exhaustion, and violence

Then, I went down another rabbit hole: it would seem that dysentery and hepatitis would be traveling companions, no? Despite the fact that one is a bacterium and one is a virus, unsanitary conditions involving waste are their common denominator. Marlo, my AI assistant, told me that I wasn’t mistaken, and that they do show up in the same places, like:

- Refugee camps

- Slums or informal settlements

- Prisons

- Plantation quarters (historically)

- Field encampments in war zones

- Even today, natural disaster zones with damaged infrastructure

Then—from this—I started searching for exhaustion-related diseases and deaths. That’s when the lightbulb came on!

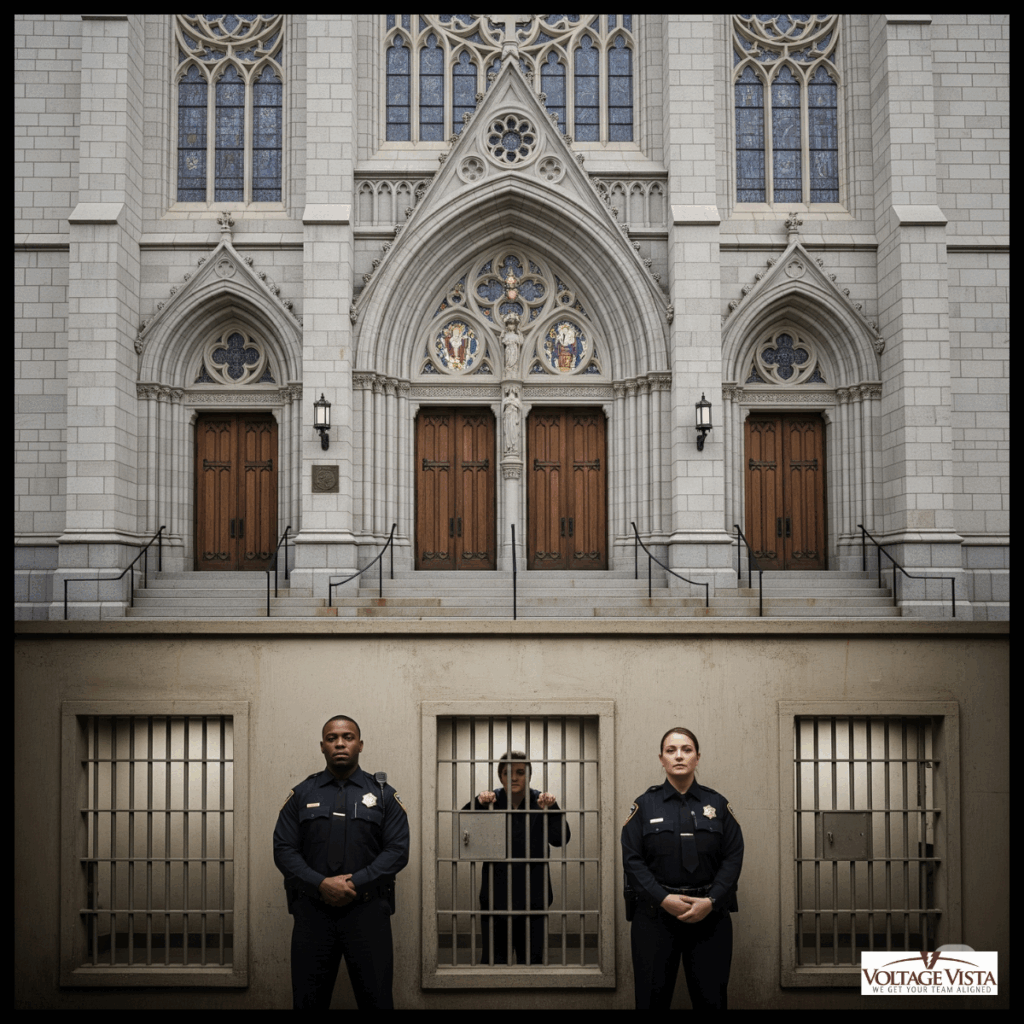

For 10 years, I provided harassment prevention training in a jail and learned that many of the correctional officers had poor health outcomes and often died shortly after retirement (I’m learning that some of these challenges apply to public transit workers, too.). This was a significant experience in leadership and structural harm.

I also learned that working in a jail is just like being incarcerated, because you’re exposed to the same conditions. Initially, I focused on the loss of freedoms—i.e., I couldn’t bring in my own water bottle or lip balm, had to carry a clear bag so everyone could see my tampons, etc. On the other hand, I noticed inmates were ALWAYS cleaning up. The facility smelled like a combination of cleaning solution and plain ole funk. Additionally, the officers were adamant about NOT using the same bathrooms as inmates. I thought that was about social order and control. Now, I see all of this as a health and safety concern! When I trained there toward the tail end of COVID, I was most concerned about airborne diseases like that one and the flu. It never occurred to me that dysentery and hepatitis were also threats I needed to consider as a consultant. When you take sanitation-related diseases and add in diseases transmitted through skin-to-skin contact and “illegal” sex, prison is dangerous. I should’ve charged more for taking on that risk!

When I did my trainings, it was six weeks of going there 2–3 days a week for 8–12 hours at a time. Usually, by week three, things became emotionally challenging. I had to change my morning mental routine. Seriously, I was praying and singing in the car—“Jesus, be a fence all around me!” What’s more is that I saw similar emotional struggles in the officers. It’s hard to be in a place like that every day. And don’t even talk about that mandatory overtime. So, it’s not just daily, but 16 hours a day! On top that, their decompression tools were often counterproductive—alcohol, weed (coupled with praying not to be chosen for a random drug test), sex, spending sprees, and oversleeping (probably due to exhaustion and depression). Then, there were the suicide and divorce rates!

So, you’ve got the daily stress of knowing that going to work can make you sick—and they knew, like I did, the stats about their likelihood of suicide and mental health challenges. Now, let me add another layer.

Once, I added a piece of content that really touched and shook the officers. I talked about fight/flight/freeze/fold from the angle of being trapped with your harasser at work. In particular, I zeroed in on how many of them knew they earned great money because of the overtime and had built their lifestyles—especially home purchases—based on overtime pay. Yet, they also knew that their ability to quit but maintain the same salary level was limited. Therefore, if they quit for the sake of their overall health, they’d be, in essence, choosing a low-wage job and losing everything they’d worked for—while also losing decent health insurance. They wanted that insurance for their families, even though they often worked so many hours that they couldn’t use it.

…The More Things Change, the More They Stay the Same…

Now, as I sit with the suffering endured in the 1850s—bodies burdened by labor and denied rest—I’m struck by the continuity. Different settings. Different tools. Same architecture of entrapment. In both eras, survival demands choosing between self-preservation and system preservation. And the systems rarely honors the cost of that choice. The toll isn’t just personal – it points directly to leadership and structural harm that’s built into systems.

Finally, this is why leadership matters so much. In tough environments like these, the responsibility to plan and develop organizational culture with intentionality should not be a dreaded burden. Rather, it is an act service, love, and respect. It is the epitome of emotional abuse to expect excellence all while failing to create the circumstances to help facilitate it. Indeed, as I always say, “You cannot lead people you don’t love or care about.”