In the Grip of Chronic Stress

Three Things to Know about People and Stress that will Help EVERYBODY at Work

- People behave differently when they are operating under stress.

Their best bet for working through stress comes from the self-awareness work that they’ve done BEFORE the current stressful event. Self awareness makes a person more likely to recognize their stress response behaviors, inform others of what they are like when distressed, and reduce those behaviors.

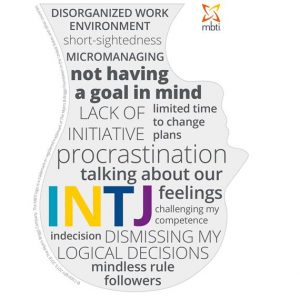

There are two instruments designed to help you and your team better manage stress. The Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) will help you get more specific insights into what stresses you and your stress responses. The MBTI has 16 personality types, and the image provides example of type specific stressors. Additionally, the MBT offers a Stress Report (click here to see mine as an example) to give individuals insights into how their behaviors change when stressed: wouldn’t it be great if more people knew their stress behaviors and informed the rest of us so that we’d know how to help or when to steer clear! On the other hand,the Thomas-Kilman Conflict Assessment helps people to understand their typical conflict responses. You might ask, “What does conflict have to do with stress?” When people are stressed, they are less able to control their impulsive responses to conflict and are therefore less likely to manage conflict as well as they normally do. Specifically, this tool helps teams better understand how they function as individuals and collectively. Once, I worked with a team that gained tremendous insight into their inability to get buy-in because they realized that nearly everyone on their team defaulted to avoidance during times of conflict. If everybody is avoiding conflict, they aren’t effectively vetting ideas.

There are two instruments designed to help you and your team better manage stress. The Myers Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) will help you get more specific insights into what stresses you and your stress responses. The MBTI has 16 personality types, and the image provides example of type specific stressors. Additionally, the MBT offers a Stress Report (click here to see mine as an example) to give individuals insights into how their behaviors change when stressed: wouldn’t it be great if more people knew their stress behaviors and informed the rest of us so that we’d know how to help or when to steer clear! On the other hand,the Thomas-Kilman Conflict Assessment helps people to understand their typical conflict responses. You might ask, “What does conflict have to do with stress?” When people are stressed, they are less able to control their impulsive responses to conflict and are therefore less likely to manage conflict as well as they normally do. Specifically, this tool helps teams better understand how they function as individuals and collectively. Once, I worked with a team that gained tremendous insight into their inability to get buy-in because they realized that nearly everyone on their team defaulted to avoidance during times of conflict. If everybody is avoiding conflict, they aren’t effectively vetting ideas.

2. People need some stress

Stress is the pilot light of motivation. A little or a controlled fire keeps us moving; however, a raging forest fire will overtake us. There’s a balance between too much and too little stress. With too little stress, you’ll likely see a disengaged person and an environment in which the goals and accountability are lacking. Where there’s too much stress, you’re likely to see a range of behaviors, depending on the person. People respond to stress by entering into the body’s automatic fight, flight, or freeze responses because the stressor is interpreted as a threat. Overwhelmed people tend to behave in a manner designed to “make it stop” or make the threat go away. In both cases, the person’s subconscious perception of the situation, what they believe is likely to happen to them, informs their behavior. Too little stress = nothing will happen to me. Too much stress = whatever happens to me will be terrible.

3. People manage stress better when they have a plan

For what to do when they are in the grip of stress. As you study your team, both as a collective unit and as individuals, you can anticipate stressors like the ones below. As you consider individual stressors, bear in mind that their impact will be magnified if they occur in tandem with other stressors or are accompanied by conflict. Finally, when you embrace and discuss the realities of stress and your workplace, you increase the likelihood that team members will discuss their challenges, experience greater psychological safety and participate in meaningful conversations about stress management remedies, which improve your organizational culture.

| Regular Work Place Stressors | Pandemic-Related Stressors | Personal Stressors | |

| Annual obligations (i.e., budgets, grant and compliance reports, etc.). | Unclear goals or deadlines. | Fear of personally contracting the disease and/or loved ones becoming sick. | Chronic health problems, including mental health challenges. |

| Chronically heavy workload/perpetual long hours. | Harassment. | Economic shifts that have impacts on personal finances. | Financial difficulties and unexpected expenses.

|

| Responsibility for vital work, but not having all of the tools to manage the responsibility. | Change – responding to shifts in the market, regulation or litigation.

Policy and procedure changes, including new systems and software. |

Rapid and disruptive changes in a remote environment that impact workload, communication, and motivation (overwhelm and “does this really matter?”). | Change – marriage, divorce, moving, death. |

| Ongoing conflict with a superior or colleague. | Contingent work status, i.e., annually renewed grant-funded positions. | Childcare. | Demands of family life. |